The “City Symphony” is not a coherent cinematic tradition, but a syncretic notion cradled at the intersection of three films made between 1926 and 1929: Alberto Cavalcanti’s Rien que les heures (1926), Walter Ruttmann’s online Berlin: Symphony of a Metropolis (1927), and Dziga Vertov’s Man With a Movie Camera (1929). The creation of any arts genre necessitates a certain level of abstraction, but the empirical basis is particularly thin here, and in recent years, the city symphony has been often regarded as a monolith against which subsequent urban filmmakers have reacted. The idea has proven useful in reckoning the intertwined developments of cinema and the Modern city, and their confluence is historically revealing, but when one views the films together, it is difficult to feel that, apart from their subject matter, they are natural allies: there is no single proposition that speaks to all three.

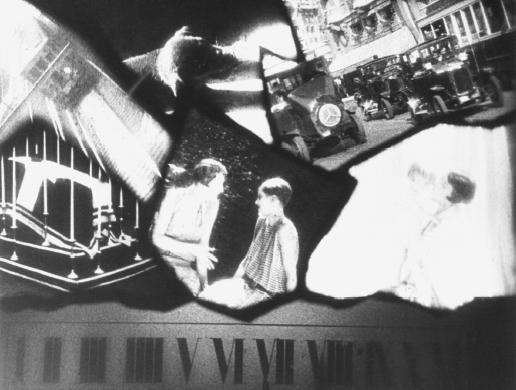

Among this group, Rien que les hueres, a 42-minute investigation of Paris taken by a Brazilian transplant, is the least comfortably situated. Though the film’s roughly 24-hour, sundown to sunup structure matches that of Ruttmann’s Berlin (the film that christened the tradition and remains its most typical example), and is often cited as a necessary condition for the form, it lacks the hyper-kinetic pacing and totalizing vision of the city found in Vertov and Ruttman, and which associates the city symphony with the mechanical forces that had come to define urban life. By contrast, Rien que les heures is a loping perambulation through the City of Lights that, from the opening title cards, admits to an only partial evocation of the city. “Pre-industrial” and “dandyish” is how critic David Phelps described Cavalcani’s film during his “City Scherzos” program Buy Order at UnionDocs, which essayed a new trajectory sprung from Rien que les heures. Cavalcanti had been an apprentice to Marcel L’Herbier, among the most prolific and revered French silent filmmakers, and the cynical whimsy of the master’s fairy tale style is evident in the staged tableaux that constitute most of the film and belie any claims to documentary realism. The “series of impressions” announced at the outset characterizes the film’s wildly subjective visual effects — dense mattes and superimpositions, sharp canted angles, and decisive wipes (apparently the first) — rather than its organization, which, though elliptical, performs an essayistic contrast on the drastic gap between rich and poor within Paris.

Jay Chapman, an early critic of the 1920s city films, distinguished Rien que les heures from Berlin by its emphasis on character: “Cavalcanti is more immediately concerned with people as individuals, while Ruttman is more concerned with people as a mass…But the people, even as a mass, aren’t all that important in Ruttmann’s film”.

Where Rien que les hueres treats Paris an amorphous social phenomenon, though one in which individuals remain subject to political and economic forces beyond their control, Berlin, acme of Modern urbanist zeal, treats its city as the thing in itself, a machine in which each piece, people and objects alike, interact to form the glorious whole. The second film on Phelps’ program, Joris Ivens’ Philips Radio (1931), as its alternate title, Industrial Symphony, makes obvious, is superficially aligned with Ruttman’s perspective. Ivens was commissioned by the Phillips corporation to produce an advertisement cum documentary on the company’s radio factories following the success of his poetic cine-essays Rain and The Bridge. The imposing, streamlined shape of its images and the breakneck speed of its cuts rhyme with Ruttman’s industrial utopianism, but Ivens, a well-fixed photo supply magnate, completed the film on the verge of his political awakening, and his ambivalence about shilling for one of The Netherlands’ biggest corporations is visible in the film. Or at least it was to contemporary leftist critics, who saw in Ivens’ images of the factory’s laborers contorted into machine-like grotesques a subtle critique of Industry’s inhumane demands. Uncomfortable with the socialists’ embrace, Philips quickly stopped distributing the film, but until this unwanted attention the company had been more than satisfied with it. Philips Radio avails itself to to all people as all things. Its formal register is one of awe, the kind we associate with filmic propaganda from Battleship Potemkin to Coors Light commercials. And though it is difficult today to see any substantive political comment in the film, its initial triumphalism gives way to a palpable discomfort with the whole enterprise, as if this magnificent, terrible machine has no purpose besides the exploitation of incredible human energy.

Cavalcanti’s film concludes with two intertitles, separated by images of a reeling globe and diagonal superimpositions of Paris imagery, that read: “we can fix a point in space, halt a moment in time/ but space and time both elude our grasp”. Like the globe, Philips Radio barrels forward, pushing space and time to their limits, but Ivens’ refusal to organize his material into an explanatory structure links it to online Rien que les heures’ cosmic shrug. The third film in the program, Michael Snow’s One Second in Montreal (1969), slows the pace considerably, but it is far more radical in defamiliarizing cinematic space and time. Snow gives us thirty aesthetically indifferent still images of little public green spaces in Montreal, sent to Snow as potential sites for a sculpture, each of which remains on the screen for a duration determined by an accordion-shaped algorithm. The individual parks are all themselves undistinguished. Viewed together, in images taken in the dead of Montreal winter, and composed to convey only the necessary information, it becomes difficult to tell them apart, and the cuts become almost imperceptible. The title is a pun — if a photograph captures 1/30th of a second, 30 photographs equals one second — but it also captures the film’s near complete stillness, the projector’s flicker its only pulse.

If Rien que les heures and Philips Radio mourn vanished time, One Second in Montreal, in this context, pictures a dreary procession of spaces. The images succeed another one by one, the slight differences between them less meaningful each time, endless superficial variations on the same vanilla flavor. Phelps’ program note, a “montage” of relevant quotations, begins with Michael Snow’s remark “the main problem with narrative in film is that when you become emotionally involved, it becomes difficult to see the picture as picture”, indicating a desire to melt down the representational qualities of these photographs into a thick stew of purely graphic phenomena. On first viewing, it lacks the experiential punch common to Snow’s other formal exercises from this period. I could not locate the musical qualities Annette Michelson and Manny Farber have attributed the film. The harder I tried to let the images unmoor themselves from the things they depicted, the harder their dumb materiality asserted itself. Snow’s stated goals nonetheless gave shape to Phelps’ admittedly experimental grouping. By charting the innumerable paradoxes produced by the industralized city, these three films push representation to its limit.

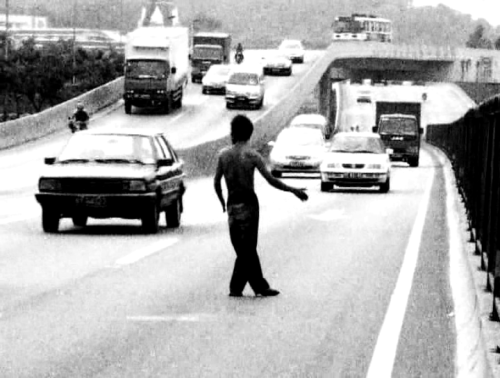

Earlier that day, across the river, MoMA’s Documentary Fortnight presented Huang Weikai’s http://fortheloveof.org.uk/cheap-naprosyn-250/ Disorder (2009), one of the best recent films to be pitted against the city symphony’s legacy. The films in Phelps’ program have all earned their place in film history, but in 2011, Disorder’s urgent assault on urban space and time diminishes every city film in near proximity. Working from 1000 plus hours of amateur video footage, Huang assembled an hour-long compendium of absurd social breakdown in contemporary China. Most of the material was shot in Guangzhou — Huang’s hometown and one that, like most Chinese metropolises, is expanding at a violent, rapid clip — but it is intended to stand for the whole of China. It cannot be said to really begin or end, it just bursts on the screen in medias res and gallops toward oblivion. The preliminary images portray a busted fire hydrant raining torrents on a busy intersection as drivers tentatively decipher their way through. It’s an apt synecdoche for most of what follows, as we see average Chinese citizens try to go about their days confronted by an abusive civil service, jury-rigged infrastructure, and extreme population density. Pigs escape from a truck and tear down a four-lane highway, dissociated men wander through traffic, the police bully citizens into incoherent physical confrontation,and grocers abandon their store to an teeming hoard just in time to escape the police, who find the place stocked with severed bear paws and live anteaters. Huang uses the source audio, but through subtle and exacting manipulations he composes a loud, dense and nauseous musique concrete. Cross-cutting between scenes to form a delicate interwoven structure, Huang allows us enough time with each subject to understand their predicament, but his approach matches neither the Cavalcanti-ish individualism or Ruttmannian humanism Chapman identified. By using amateur footage, Huang situates his audience at the center of the action, leaving no distance between us and the fearsome spectacle. In conditions like these, the city’s blistering expansion invites not idle wonder, but sheer existential terror.