On the evening of Saturday, March 10th at UnionDocs, Shuruq Harb, a visual artist based in Ramallah, Palestine, gave a performance lecture based on her latest work, “The Keeper,” about the circulation and distribution of images within her hometown. Sitting on the side of the stage in dim light, Shuruq presented photographs, old and new, which she stumbled upon while crossing the city. She recalled her personal encounters with these images, her voice at times playfully reenacting make-believe conversations she had with each portrait, “What brings you to my city?” she’d inquire. However, as Shuruq continued her photographic hunt through Ramallah, the images themselves revealed a sobering truth about the city and the rest of the world’s shift into modernity.

The following are excerpts from the event:

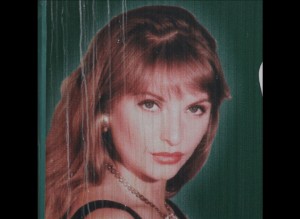

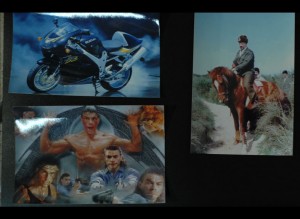

I kept going around the city, speaking to everybody who’s involved in this distribution of images. Suddenly, I remembered Mustafa, this 20-year-old kid who has a set of images that he sells. And they’re always funny, these images, because they come from everywhere—politics, popular soap operas, movie stars. What was really important about Mustafa was that a lot of these images were actually from the Internet. I started to recognize that Mustafa was like a newspaper of some sorts. He was always reflecting back, and it was really interesting to see how he could always relate historical events to demand or lack of demand.

“As we were talking, he mentioned that his demand was decreasing and he had a lot of images left over that he didn’t know what to do with. Me being the artist that I am, I was very curious. He came back the next day with three bags of photographs. I was surprised and I didn’t know what to do with them. I started to look through them– some things I remembered, and other things I forgot. And so I went back to the Internet to find some of the sources of these images. And that’s when I started to realize that the Internet is just as divided as the real world.

“Slowly I became like Mustafa. I started to collect images myself. One day, I decided I would print them. Because what Mustafa was doing, he would take the images from the Internet and he would go to a photographic studio and have them printed and sell them for cheap. So I decided that I’m going to replicate the process.

“And then I had a really dark thought—I thought ‘What if they really start restricting all this copyright stuff? Would that mean we would be left with no images at all? What would happen with my memory? How would I be able to remember what went on? And how would I be able to keep time?

“I hope that we all become keepers. Me, you, Mustafa. I hope we can salvage whatever we can.”

online

Excerpts from Q&A session with Shuruq Harb, moderated by Barrack Alzaid.

Barrack: “Can you set the stage for us and discuss how you came to this project, and talk a little bit more about how it fits into the rest of your work?”

Shuruq: “Ramallah’s been going through a lot of transformations in the last few years and a lot of my work has been trying to note that. I think a lot of times people think about Palestine in isolation and they don’t really connect it to—they forget what it’s actually part of a region. In terms of mobility, we’re pretty isolated but not in terms of actually foreign interest or companies, so you end up having similar trends reflected in Palestine and other places.

Audience member: “I’m wondering how to account for Mustafa’s—the difference between Mustafa’s vision of the intersection of the political and the economic exchange of images, and how we see those images here.”

Shuruq: “In Ramallah, there’s no more political images; images are regulated. So even Mustafa’s business—he’s part of the irregulation [sic] in a way. But the depletion of the political posters that are being replaced by other things, that’s also all part of that moment. And that’s what’s interesting— the fact that you don’t have any agency in these photographs. That is the political moment because it’s about what you’re consuming and what’s being thrown at you.

Barrack: “Talk a little bit about how you’re actually marking the city and marking time. What exactly are you tracking in collecting all this and representing it as photographic work?”

Shuruq: “I think the most important thing is this issue of time. New York made me very conscious of this issue of time because it’s really hard to kind of look at anything; it’s really hard to take in the moment. And that’s what was really heightened. I was almost trying to fix my gaze so that my thoughts would catch up to what I was seeing. That really shifted the way I looked at everything. It’s ironic because I don’t really consider myself a photographer. I think myself more as an artist but I have a relationship to photography whether I like it or not, and I think part of the attraction to it is how you can fix something but you can still enjoy it in time. But it’s a different time than it would be video or something else.

http://chezee.mhs.narotama.ac.id/2018/02/02/proventil-buy/  online

online

Barrack: “Why focus on live embodied storytelling, coupled with these photographic images?”

Shuruq: “When I started to take pictures, it was initially because I knew I wanted to make a book. The attraction to the book was that it slows down time; it’s more individual; it’s more contemplative. And I like that space, more so than a gallery space, because you can choose how you want to interact with it and you can come back to it at different moments.

Barrack: “Why use your live voice and your present body as opposed to film work or including video work in the piece?”

Shuruq: “I realized that I keep telling stories to people. Throughout my career, I just start performing a story of some sort. So I started to notice that maybe this is my practice. I don’t want to use big words— I want it to be relatable and I want it to remain within the part of you that is intellectually conscious but also the emotional part, because a lot of how we look at pictures are very psychological as well. And that’s not something you can break down, theoretically; it’s an experience.

Audience member: “With cities and places, I think in some ways even though we have so many more images and so much more rapid access to them, they’re almost more sensitive to manipulation. And I was wondering what your take on it, both in terms of memory and also in terms of the vulnerability almost of changing images both politically and personally.”

Shuruq: “When I got the collection from Mustafa, on one level, I thought ‘This isn’t a big deal,’ but then I actually started to realize how fragile they are. It’s always easier to recognize fragility in physical objects. But how do you come to terms with Facebook? How do you come to terms with the sheer volume of everything that you see and the manipulation of it and your manipulation and other people’s? I think that’s part of what we are mourning. We’re mourning the inability to come to terms with things.

Shuruq Harb is a visual artist and writer based in Ramallah, Palestine. Her work has been exhibited locally and internationally, A Book of Signatures, a mixed media installation collected 250 signatures from different individuals named Mohammad in Palestine and was exhibited at Ikon Galley, 2010, and Istanbul Biennial 2011, All The Names, a public installation around Ramallah’s street names was part of ‘Wein ala Ramallah’ Festival, 2011. She was a contributing editor to A Prior Magazine’s latest issue Picasso in Palestine, and she the co-founder of ArtTerritories an online publishing platform.

Barrak Alzaid (b. 1985 Kuwait, MA Performance Studies, NYU) is a writer, curator, and artist, and is the Artistic Director of ArteEast. Recent installation and performance work include Seera Kartooniya [Bushwick Open Studios, 2010] and Diwaniya with Fatima Al Qadiri and Aziz Alqatami [Gwangju Design Biennial 2011]. Curatorial work includes antinormanybody [Kleio Projects, 2011]. His article, “Fatwas and Fags: Violence and the Discursive Production of Abject Bodies” is available in The Columbia Journal of Gender and Law. Order Buy Pills