Omar has never been to the ocean before. He lives in a homeless shelter in the center of the metropolitan port city of Karachi, Pakistan among a group of similar child-aged orphans. These Birds Walk, Purchase the debut feature from filmmakers Omar Mullick and Bassam Tariq, opens with Omar’s (orphan, not filmmaker) first encounter with the sea. Without any indication of who this child is he is seen charging at the low waves of an evening tide. It is an image that resonates with significance without any prior context—its imagery could easily be read in its allusion to conflicts of man vs. nature, the hostility of the ocean, the sublime qualities of an endless horizon, etc. etc. The symbolic qualities infused in the image make it a near textbook opening shot. However, while the film’s opening image is ripe with relevant allusion, there is something disconcerting about its inclusion here. It is a fantastic opening shot, but perhaps for the wrong film given what follows.

These Birds Walk Cheap is an examination of homelessness filmed in a style that has been described by a number of critics as “lyrical”. This adjective, while being notorious for its vague and nondescript definition, does seem to be fitting in reference to this film because it is one that works against the dominant realist tradition. Its distinct style—at times providing moments of beauty, at others moments of great frustration—make the film incredibly difficult to place in any accepted genre. In many ways Buy Cheap These Birds Walk Order Pills plays like a work of fiction, which is often an aspiration of documentary film, but the seemingly fictional aspects of the film stem from its aesthetic choices, thereby diminishing its emotional impact. At 71 minutes the film runs smoothly through its particular tale of homelessness in Karachi, but it is this very narrative success that produces a stark feeling of uneasiness about its appeal as a “lyrical” documentary film.

From the opening moments of the film Omar appears to be emotionally tough well beyond his years. His case is particular among the orphans we see among the homeless shelter at which he lives: while most children there have been abandoned, Omar’s homelessness is self-imposed—he has run away because of an undesirable home life. He exhibits throughout the film an inveterate desire for attention that appears manifest itself through the physical and emotional dominance he asserts over the other children.

Or at least the camera characterizes Omar in this way. We never hear the other children describe Omar’s personality; it is only observed from what is caught on film. For a child who lost his parents at such a formative age, the role the camera occupies in his life must be brought into question. Omar is indeed a child who lacks recognition from the world, and ever more so in the lack of parental figures guiding him through his development. The camera, helmed by two adult Pakistani men, acts as a surrogate for the specular role a parental figure normally provides. Omar is clearly aware of the attention that the camera allows him. Order One must wonder if a lack of recognition was an impetus for Omar to leave home in the first place.

During a scene around midway through the film the children of the orphanage are led in prayer by one of the older children of the group. The children kneel and face the direction of Mecca. The camera, in this quiet moment, faces the children in a wide angle shot. We see Omar take note of the camera, and the harrowing situation that follows seems to have precipitated from the vanity that the camera inspires. Lead by the prayer leader, the children bow their heads to the ground, they sit back up and another prayer is given, they bow again, but this time Omar doesn’t. He reaches his body over towards a child to his left and smacks the back of his head while he prays. A few children in the back laugh at Omar’s antic and on the bow proceeding the next prayer the child gives his retort, slapping Omar on the back of his head. Children will be children, of course, and especially without guidance through such a young age. But then the film cuts to a medium shot of a child nearby Omar and, as if he has given up on waiting for a response from God, he breaks out into tears and cries out for his home. On its own this moment is absolutely devastating. The child appears to not yet be ten years old and the pain of living has become too much for him to bear, even in the midst of performing an act that is supposed to bring him comfort. Yet the shot of this incredible moment lasts for a few seconds before it is cut to bring about the next scene. What seems to have dominated this scene is not the gravity of the crying child, but Omar. And then, as if to clear the stage for Omar, the devastated child disappears from the film—in a scene evidently not captured on film the child is taken home by his parents.

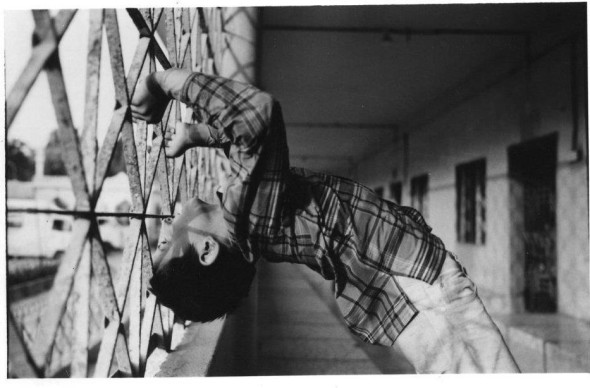

The film’s surfeit of highly composed shots prop up its “lyricism” and create an atmosphere of affectation. Dramatic low angle shots of children’s faces are set against a sunny Pakistani sky; the camera moves along with children as they run about; and the camera even captures a moment of Omar praying to himself in bed under the dim light of one candle. But what are we to make of such a private moment in a film that makes such a habit of stylizing its supposedly “real” content? In the context of the film the scene of Omar praying before he sleeps comes off as a moment produced by the presence of the camera itself; given how close we are to Omar he must surely know that the camera is there. Like the cargo cultsof the post-war era, Omar seems to have an almost religious connection with the foreign object that has suddenly become such a large presence in his life. He thrives on the attention that it continually gives him—it literally allows him to be recognized in an environment that otherwise refuses to do so. The effect of the camera on Omar’s behavior is seen most poignantly in a scene which depicts a fight between Omar and another child that has escalated beyond mere child’s play. Eventually an older and physically stronger child breaks the fight up and restrains Omar as his anger continues to rage on. And here we see the confirmation of what has been feared all along—that what is occurring on screen is not as authentic as we would like it to be: the older children says to Omar that he is just acting up for attention from the camera. Now at Omar’s bedtime prayer scene the authenticity of his highly mature soliloquy falls apart. The relevance and poignancy of what he says is truly remarkable. He lies on the ground as he asks God if he should kill himself to rid the loneliness he carries with him. For a child not yet ten years old to be caught in the gravity of his own despair at such a young age is truly a dramatic event. On the surface, like the previous prayer room scene, the moment appears too real to be fake, but once again the stylizations of the film prompt this disturbing feeling that there is much more inauthenticity laying deep within this seemingly “real” moment. The scene, however, is shot in one long take, which is a tenant of realism. In juxtaposition with the stylized aesthetic of most of the film this scene does not provide the depth it seems that it should have provided, and once again content is compromised to clear way for the discomforts of an aesthetic style.

As has already been made clear by the enthusiastic response to this film, many people may not find any issue in its “lyrical” aesthetic. Even when considering the troublesome style of These Birds Walk filmmakers Mullick and Tariq do succeed in providing a perspective of homelessness that does not feel limited to their subject—that is, what they communicate about the experience of homelessness is not made to appear to be specific to the case of Omar. Nor does the film reduce its subjects to political props; Omar’s humanity is preserved as one, even for a young child, that resists being fully encapsulated by a reductive message. But, returning to the film’s opening, to begin a film with a shot that feels so composed and so tendentious in its allusions seems to almost detract from the story that Omar tells, one that perhaps could be communicated without such an affected universalizng. The film truly suffers from such an approach—what humanity is found in tender moments seems to fade beneath the ornaments of the aesthetic. These Birds Walk is certainly deserves its label as a stylistically poetic film, but one wonders if such an approach is truly necessary with a person who already contains an ineffable aspect of poetry within himself.