A density built up of transparencies” is one way of looking at cameraless works like Color Series and Veils by Madison Brookshire. On Saturday November 2nd, 2013 Brookshire screened Color Series (2010), a cameraless work consisting of six films that can play independently or in small groups, and Veils, a hand-made, paint soaked film work-in-progress that allows evaporation, dust, crystallization, mold, and more to inform the image. Brookshire was joined for a post-screening discussion by writers Leo Goldsmith, Genevieve Yue, and Gregory Zinman. The discussion delves into the technical processes in creating cameraless works, the perspective of the artist, and most pointedly in the temporal experience of the audience, and interrogates the sociality of the cinema experience. The discussion also included contributions from filmmakers Ken Jacobs and Bruce McClure along with UnionDocs Collaborative fellow Anne-Katrine Hansen and Programming team member Aris Dilone.

Leo Goldsmith: I help curate a small gallery space in Greenpoint called Heliopolis and we did a show with Madison called buy cardizem la 180 mg A Color Box. I’ll let Genevieve and Greg talk about the film’s historical context and the more interesting affective responses we just enjoyed, but my involvement in the work is curatorial. so I thought it would be interesting to show some slides.

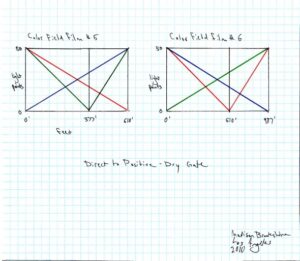

A Color Box featured moving image works dealing with color in some regard, including work by some local heros like Kenny Curwood, Sandra Gibson and Bill Brand along with Pierre Abere and Eric Ostrowski. There were some digital projections, some film projections as well, and here is actually the first film you saw, the first part of Color Series. We mounted the film over a lightbox so you could sort of go back and forth. It’s just interesting to see, and I’m interested in hearing your discussion of the differences of seeing this kind of work here and then in this context. It’s very special because it’s partly film, partly sculpture, and part high-tech-interactive installation work. I thought I’d share that as an interesting point of comparison.

Genevieve Yue: I wanted to comment on the experience of watching Color Series. This is the second time I’ve watched it. The first time, the projector was in a booth. In that case, but also tonight, I had the very distinct sense of being aware of myself but also being aware of the other people in the room and being aware of the kind of sociality this particular work invites. We do not just watch what’s happening on the screen but become acutely aware of what’s going on in the space as well. This is one of the things, Madison, you mention in the notes for the film, so I’m just going to riff on that a bit.

Another thing that was mentioned in the notes for the film was Michael Sicinski’s remarks on the ways in which our film memories spring into view when we are watching this film as well. It made me think about Hollis Frampton’s A Lecture in a particular way, because in the performance view of that work there is a kind of color field aspect to that as well. A Lecture is very much about the idea of the essential elements of what cinema is, the performance really stripping it down to just the projector, the space of the room, the beam of the light, the screen. What Color Series made me think about was the presence of the audience in the work. One thing that jumped out at me when I was revisiting the text was the use of the pronouns ‘we’ and ‘us’ and this kind of inclusive language that Frampton employs. One of his first lines is ‘we have all been here before’, and it struck me as really interesting because it was Frampton not addressing a ‘you’ as the audience from the perspective of a filmmaker but really situating himself among the audience as a part of this inclusive space. It caused me to think—and this is maybe an unorthodox reading of Frampton—but it made me think about the ways in which sociality becomes a sort of structural element in cinema. One thing though that I think is an interesting point of departure—and this connects to the second work that you showed, Veils—is that Frampton describes the cinema as an “infallible performer”. So the technological apparatus for him is a kind of perfect system, but in Veils we have a sense of the frailty, as you said earlier of the film, of the material itself and of its preciousness.

Gregory Zinman: My interest in Madison’s work really comes from the fact that I do research on artists over a long historical period using a variety of media who’ve sought to make color abstractions in time. And I’m writing a book about handmade moving image practices that extend from innovations in the 19th century in color organs to the graphic cinema in the 1920’s in Europe, from post-war kinetic art to psychedelic light shows in the 1960’s, from the development of video synthesizers to current handmade work like Veils that sort of exists within and against the current digital cinema. I’m interested in the question of why the handmade persists in the 21st century, and one of the things, Madison, that I think you do so productively is to get us to think about these questions of ontology. These questions of what cinema is, or can be in relation to other arts, because I think there’s a way in which it’s so medium-specific: your use of the lab and your direct intervention into the use of the celluloid.

Then in other aspects I find your work so associative: that film memory you spoke of, and then I also think of painting. Its very hard for me in some of the blue sections of Color Series not to think of, not only of Derek Jarman’s Blue, but also of Yves Klein’s International Blue, of nominating of a color under an artist’s name. Because when I watch Color Series, I kind of drift in and out of trying to understand what my vision is doing, and trying to name the color I’m seeing. One of the things the film does so productively is that in our everyday world we don’t see color change in time. Color is static all around us. This made me think of what Robert Motherwell said: that a color field painter talks about abstraction as a way of reminding us of the need for new aesthetic experiences that are not in the everyday. By taking us out of the everyday this way—and he has a nice term—he says its a “sensuous bridge between us and the world” that gets us to look again.

Carolee Schneemann has this idea that an aesthetic object that at first seems to be too much, or to be overwhelming, is actually the work that gets us to engage the most and question the most. It stays with us, and we learn from that experience. Veils, which comes at us with 24 frames of changing abstraction is perceptually overwhelming, at least for me. We have all these ways of dealing with abstraction in a painting, in a single image. In cinema though, aside from Madison, I don’t think anyone in this room could give a sequential account of what happens in Veils. You can’t recount it. It’s cinema that resists not only narrative, but also memory. It escapes memories in some really interesting ways, and those are some of the things I’m interested in.

Madison Brookshire: I’ll just start by riffing off the last thing Greg mentioned. Veils came out of an interest in trying to produce a similar quality of time that I was experiencing in Color Series, but in a handmade way. Color Series is entirely industrially produced: it’s made in the lab, I work with a technician, and it’s just machines shining lights on film. I wanted to see if I could create similar plateaus or floating planes. Of course in Color Series, the changes are very structural, the shifts are graphed and gradual. In Veils its a slightly different kind of timing, because to me it’s like flat planes of time and there’s depth available in that.

I was listening to a lot of La Monte Young at the time and thinking about what makes that music special and powerful. You talk about resisting memory—Robert Ashley talks about composers like La Monte Young, who don’t make music that has a beginning, a middle, and an end, but they do still exist in time and yet you’re not presented with something pushing you through time. So I think, and I hope that Veils is an attempt to do something like that, but with film hand-soaked in paint, which I think is part of what contributes to that experience. It’s not quite as expressionist, even if it is affective, its not quite as expressionist as most hand-painted film tends to be.

Ken Jacobs: Madison, have you seen Color Series with sharp corners?

Madison Brookshire: Yes, when we showed it at Anthology it was all masked tightly.

Ken Jacobs: Was there a difference in experience for you?

Madison Brookshire: Yeah. Color Series is really made to be variable. It can be shown on tungsten or xenon, it’s not timed one way or the other. The experience is how the projector interprets this object at that moment, and part of that is the room. I’ve shown it on a wall in a white gallery cube, which I like very much because everything sort of glows that color. I was getting some of that here, which is interesting because it’s also very black around this edge. I do prefer the soft edges when I can do it because there’s a lot of activity on the edges, when your cones start to fatigue, or whatever it is, and your eyes shift a little as they always do. That edge becomes really active for me and that’s really where the experience is for me.

Ken Jacobs: Could you describe the difference in experience for you between the right angles and rounded corners?

Madison Brookshire: No, I don’t think I can because that’s not where the difference is for me. It’s in the border itself, not in the corners. You’ve seen it both ways: I’m assuming your question is coming from an experience…

Ken Jacobs: But I wanted to hear from you how you see it differently. In this nebulous kind of work that would be a huge difference.

Madison Brookshire: I accept those differences. I guess because it’s made to be that way. It’s also 6 films that can be shown as a whole film like this, and I’ve also shown 1 through 3, or just 5, or just 6. It’s made to be a modular work in that way, so I don’t know if i could articulate the difference, I think Bruce brought it up actually at the screening..

Bruce McClure: I would say that the difference I see is that one is like a shield, and one is like looking through a window. When you have masking around it, and it sharpens the edges up, you really feel like you are looking through something. As opposed to when its sitting here on this wall, and it has those curves, it seems to come forward. I see it that way—the difference between Robert Irwin, one of his curved things, and say a James Turrell where you’re looking into a box. I don’t say one is better than the other, I just personally prefer the presence of the light on the wall than something bound up like a mummy in masking.

Madison Brookshire: I think masking is really only useful if the shape is going to be trapezoidal. Then its better than, it’s better as a square than as a trapezoid, I know that.

Bruce McClure: You always see someone mess up something with the masking and you say ‘oh, oh’ it’s just coming in too much…and you think ‘I paid ten dollars to see this and I’m seeing nine dollars and ninety nine cents worth’.

Madison Brookshire: Well, you get all your money here. (laughter)

Bruce McClure: There’s something related to that too, the guy who wrote Smoke was talking about a twist. He described how in the process of going from a short story, to a screenplay, to a film, there was some sort of twist. I’m wondering if there are any twists. He wouldn’t tell us what they were, he was keeping it a secret, whatever twist it was. I asked him: what was the twist? He said “that’s the writers secret”. I thought that was pretty chintzy. (laughter) I was wondering if you had any twists. For one thing, the obvious one, I’m gonna answer it for you: is the twist of the focusing knob, that’s the twist.

Madison Brookshire: I know, I know, I just couldn’t get it on number six…

Bruce McClure: No, it was great, on that last one where you’re fumbling around.

Madison Brookshire: I know…I just…

Bruce McClure: No, I love that exposure. It’s like ‘uh oh I’m hanging!’, you know because the rest of the time we are looking at aberrations if you know what I mean. The black spots, or the white spots that were over here, that’s what was in focus. So in a sense you were looking at the aberrations with the rectangle behind it … I’m not complaining.

Madison Brookshire: Yeah and that’s where it is for me. Seeing the grain is actually really important in the experience of this work. So I do prefer it in focus. You still obviously get an experience but, you know it’s just like an impossible film.

Bruce McClure Order : Yeah, and I could keep going. The Frampton thing she said about the ‘perfect’…what was it?

Genevieve Yue: The ‘infallible performer’…

Bruce McClure: Yes, the ‘infallible performer’ is not the machinery. It’s the human being. It’s our eyeballs, our nervous system, you know that’s how we observe things. What’s going in: that’s the infallible…bah, whatever it is… (laughter)

Leo Goldsmith: If I could just jump in, because one thing we’ve mentioned, and mentioned in terms of Veils is this question of depth and flatness. And this is something that I experienced maybe from the back of the room, was this intense depth.

I think we’re so used to seeing the blue LCD monitor with nothing going into it that’s just this dead flatness. Whereas blue on this screen is really rich and sort of sucking you into the vortexes of grain. But also Veils: a veil is something that is kind of obscuring, or like a plane, I think you said. So maybe you could talk about the difference.

Madison Brookshire: Yes, I see these works in depth very much and of course, with something like Color Series, it goes in and out. I guess Veils goes in and out too because you’ve got some sections that are much more shallow, because there’s less information. You know I studied with Ken (Jacobs), and depth is important in that work, and Ken taught me to see depth in a number of painters whose work became very important to me. I also work at a museum and I was fortunate enough to be able to hang around and look at some painters I wouldn’t have gotten into otherwise. Painters who were working with very flat expanses of color but then incredible depth becomes available.

I’m thinking specifically of Morris Louis, Barnett Newman, Agnes Martin, Kenneth Noland to a certain extent—Agnes Martin out of all of them being the most profound in terms of what’s available: how simple the interventions seem but how rich the experience can be, how much vibration there can be. And of course it’s not just a formal experience. It’s like experiencing those things then has an affective quality, which is harder for me to describe. If it were just a formal exercise, it wouldn’t be worth it. Hopefully there’s a feeling that you get as you experience these things.

Veils is a little different because it’s not as related to those color field painters. It was prompted by the way that Deleuze writes about a kind of cinema he calls impressionist. In that section of his book he references Goethe’s Theory of Colour, and specifically that white is the ‘fortuitously opaque flash of absolute transparency’, or something like that—that you can build up a big something out of a lot of nothings. So Veils: the film is treated many different times and on both sides of the film so it really is existing on multiple planes. Then of course there are the multiple planes that are sort of fused perceptually for us as it sort of washes over us.

Gregory Zinman: It’s interesting you talk about Veils not being related to the color field painters, but I think when you mention someone like Morris Louis, or I think of Frankenthaler, who stained the canvas, as you’re staining the film, using similar material methods, which I find really intriguing. But to push you a little more on the title: a veil obscures, as Leo pointed out, but it also reveals if it is removed. So what’s being revealed to us in Veils? If it’s obscuring something, what are we being kept from?

Bruce McClure: The rectangle. (laughter)

Madison Brookshire: For me it’s a density built up of transparencies. That’s the simplest way that I can put it. I don’t think of it as veiling and unveiling, but rather these kind of moving layers. But yes, I was thinking directly of those people when I soaked the film.

Aris Dilone: I’m not familiar with the abstract or a lot of the terms you guys are using, but I do know how I felt the whole time. It’s a lot of contextualizing. It’s this feeling of like ‘how do I explain to my friends I just sat in a room and watched colors with people’. Because there’s so much going on in life in general, that to tell them, ‘yeah I’m gonna go watch this movie and its colors.’ So then you start to think about your process, your thinking process and you’re constantly questioning not only what am I watching, but what am I thinking? You start to really think and live in your head, and to remove yourself from that and just go back into the color, it’s just an ongoing conflict. Its awesome.

Madison Brookshire: That reminds me of what Genevieve was talking about cinema as a social space. It is not usually a space where people come and see something one person at a time. Thats not why we build these rooms. And I do think that is an important part of this.

The dialogue around these painters that we brought up. I didn’t realize that when I mention I was influenced by them, to some people that that would bring out all this stuff in them. They’re sort of reviled in certain sections of the art world, and it took me a while to figure out why. I think that it had to do with the philosophical difference between what the work of art is created for, and that there is some misapprehension about works of art that are truly meant to be experienced by one person at a time. Whereas with this, it really does exist for the people in the room, and it exists for us to do it together. And hopefully it’s not stressful or painful that we’re together, but that it’s fun to think about, and that it’s hilarious to watch colors change for over an hour. (laughter)

Ken Jacobs: You know, for me it was actually an opportunity to meet the rectangle and my own shift of vision. The rectangle was never your idea of a rectangle it was always changing, and I could never keep it still. The center and the edges, and everything that was going on, and all sorts of colors began to happen you know between what was there and my own head. I was not having a social experience, I was having an experience with you, the maker of this work, you know the crowd wasn’t here for me. And I would like, if possible, if you could talk about the kind of things you see when you look at this work.

Madison Brookshire: That’s my experience too. And I’m the one who watches it by myself because you make it and watch it and make adjustments and so on. But that’s my experience. Actually a lot of what I see has already been brought up so I don’t know how much to reiterate but there’s kind of a tremendous amount of depth, but it doesn’t stick around, it can disappear at any point. As you said, there is a relationship between the color as it exists on the screen, and the color as we see it, and that’s an intriguing relationship. You start to realize that what you see is this interpretation, an unconsciously happening interpretation of what’s happening in the world. I try not to talk about this stuff, frankly, because that’s sort of the mystery of watching the film. I’m much more comfortable talking about the technical little bits of it…

Ken Jacobs: I think thats where the film is. Otherwise you’re thinking about it.

Madison Brookshire: But you had that experience.

Ken Jacobs: I had that experience, but I don’t hear it being discussed here.

Madison Brookshire: That’s what I was saying: the depth you see is not just a formal quality. Its an affective quality. So I guess what I heard in your comment was the affective quality of seeing these things and recognizing—I don’t want to say the limits of perception, because that sounds like too much—but starting to begin to understand the borders, and the way in which we experience things and even where those experiences might break down. For me the last blue one, which at a certain point appears to get darker than the room, and doesn’t stay there because it appears to then get brighter, but I know because I wrote the thing, that it is getting darker. That’s an interesting thing for me to experience. That there’s a way that we meet the work, with ourselves and with our bodies, the way that light hits and affects our bodies. This is a work that allows us to go into that for some time.

I think there’s something to be gained by having to sit and wrestle with these things. The other thing we haven’t brought up yet is that each of the six films feels very different because of the rate of change being different. So there are different qualities of time available, and available to be felt. And the way that we feel it is by the light hitting our bodies if that makes sense, including our eyes.

Anne-Katrine Hansen: Have you seen it without having the sound of the projector there? Because at some point I covered my ears and it made the experience totally different. It kind of, well the time rolling kind of stopped, it became more flat.

Madison Brookshire: Yeah, I’ve shown it in theaters that have sound proof booths, and usually when they’re doing that it’s because the projector is larger. So there’s another experience that’s available there because the image is brighter and it looks different. I like the projector in the room because, well I mean I like drone music, so the projector is this sort of mechanical performer for the piece. But again it’s modular and both experiences are available.

Audience Member 1: I have a comment about Veils, and couple questions about Color Series. What stood out to me with Veils maybe more so than with other films of that kind was the awareness of the film as a continuous strip in vertical motion as opposed to a series of images.

As for Color Series, for me, it was an endurance test, as I imagine it would be for many viewers. Did you set out to make an endurance test and also I’d like to hear more about the process. You said you sent instructions to the lab, and I’m just curious about that.

Also, is it a post-digital film? Is it something that could have or would have been done before the technology that we have now to work with color?

Madison Brookshire: It’s a computer-generated film in that the things that run the timing lights at labs are very simple computers, run by punch cards to a certain extent. What we were actually doing was running a computer program to tell the lights what to do over the film. At the lab you usually have a negative, then you have the print stock and you shine light through the negative to make a positive print. That’s how most things are made. There are three lights to do that: you have red, green, and blue so that you can adjust if you want something warmer, they can increase one of the lights in order to make that happen with the positive. In this film there is just no intervening negative, there is just print stock and I’d ask them to adjust the lights up or down according to a diagram. I’d send a diagram to the timer and he would write the program and then we’d go and kind of check together that the program was doing what the diagram asked it to do. It’s just like simple math, really simple math. And then the scale on which those lights move is zero to fifty so it’s a computer program that can interpolate between—because obviously when you get to something twenty-seven minutes long there’s many more than fifty steps being expressed so that requires a computer to interpolate those fractional increments, if that makes sense.

It’s not a digital film obviously, its very celluloid, and chemical and light. But it’s not something that could have been made a long time ago. At least not like this. Although there is a precedent but it looks different because it was made in a different way because it was made at a different time.

The strip running through the projector that you brought up: Color Series is the same, but maybe conceptually so, which is why we showed it at a gallery just over a lightbox. Because it’s just a surface essentially, it’s just material. If you scroll it over the lightbox you see the same changes in colors because you don’t need a device intervening to make it into discrete images, such that it is a reinterpreted as moving images in our brain. Its obviously not as perceptually interesting or overwhelming, or however you want to think about it. And then Veils might be similar because it’s just strips of film that have been treated and then stuck together but it’s not something that was ever created with discrete images.

Audience Member 1: And the ‘endurance test’…

Madison Brookshire: Oh, yeah… (laughter) thanks, and that’s a good question. I find this pleasurable to watch and I didn’t make it as a provocation. I do realize it’s not going to be everyone’s idea of a good time. But you know, I like grey paintings and monotone music. This fits in with a bunch of things I find interesting, so I presume that there are other people who will find them interesting too. Endurance is an interesting word because it has the word ‘dure’ inside of it which is maybe the quality of time I was actually hoping for. I wanted to make a movie about time, and then I thought that interacting with color over time might be a rather direct way to get to time, if that’s not too cryptic.

Genevieve Yue: I think this is interesting in light of what Greg said: that with abstract images, it’s actually really hard to hold on to what just happened. I don’t recall the sequence, I know there were different periods and motions but I could not reconstruct what just happened in Color Series or Veils. There is an elusive quality of attention that you’re bringing, that you’re describing. On one hand you’re feeling called into being very attentive but on the other hand, your faculty of memory is entirely illusive in a sense.

Gregory Zinman: This goes back to it’s sociality. It’s an event. It’s different than seeing Citizen Kane where its going to be the same experience most times. Getting into what Genevieve was talking about, even if it is just this one time for you, it is this experience. It’s an event that escapes many other forms of cinema, and that’s one of the things I find so rewarding about this is that you only do get it that one time. You do have to make the most of your time with it, which is the invitation of Color Series Order .

Order Ken Jacobs: To me it was really a crazy thing. I know it’s a fairly still image. I was seated up front and I was never able to see a rectangle in front of me it was always a crazy shape. My eyes were moving and things were changing. I saw all kinds of illusions and I wondered, did you put these silver things in there? I’m sure not, but it generates multiple illusions and I’ve never had the opportunity to deal with the entire screen before.

Madison Brookshire: I had the same experience when I was focusing number 6, and I was like this is hilarious I’m hallucinating how am I supposed to do this? (laughter) It’s changing colors, it’s malforming.

Audience Member 4: The idea of it being a social experience: I feel like it’s social because we are together, but at the same time it is so intense for you. You are kind of fighting yourself while you’re trying to watch it, and it forces you to ask: why don’t we see the world like this? After seeing something like this, I feel more awake, and I’m wondering if it will be a different perception for me to see color outside because of this movie. To me that takes away the social aspect because I feel like I was entirely within myself. I’m sure everyone in the room experienced it differently because it is your perception of what you are seeing.

Madison Brookshire: That makes a lot of sense to me—the coming in and coming out. Maybe “social” isn’t quite the right word for it, but the fact is that you’re involved with the space you’re in.

I am reminded of—and I don’t want to narrativize the experience—when I was in graduate school, there was this class we took with James Benning called “Looking and Listening.” One day we just had to show up at school at four o’clock in the morning. We got in a van and we drive, and drive, and drive, and we get out and he’s like ‘follow me’ and nobody’s allowed to talk, and it was completely dark. It was a moonless night. Then we were seated, and he makes sure that we are all far enough away so that we aren’t going to disturb one another, but it’s a class, we are together. We are alone together, so to speak. And then the sky slowly, very slowly, you couldn’t stay focused on it, you couldn’t watch it happen but the sky started to change. It was this cloudless, it was this pure field of slowly changing color and it was an amazing experience. And it was a struggle. It wasn’t like taking a walk in the woods when the leaves are in their autumn splendor or something. You really had to be there. So I don’t want to say that experience inspired this one, but there are maybe shared qualities between those experiences.

Audience Member 5: With Veils I noticed you’re working with smaller strips of film then splicing them together. I’m wondering what you think the limitations and possibilities are, in terms of working with time and constructing a sense of time, with one strip of film, like this, as compared to using a computer code.

Madison Brookshire: If I were to add on to it, it would just be longer, and it would be like what you saw at the end. I don’t know what other people see, but it does kind of ramp up for me at the end. It was created more or less chronologically, so as I tried different things, I got better at it. The experience at the end is actually more intense for me than it is at the beginning. And I like that beginning. I’ve tried kind of jumping in in the middle and it doesn’t work as well. It’s nice to have this kind of low-level plateau. I experience it as ten or twelve plateaus basically. I would just keep adding plateaus, and I’m not sure I’m going to.

It takes a lot of time. This is two years worth of work basically. They all soak—the paint, urine, and everything else that’s in there evaporates. That damages the film, so another part of the process is that I’m running it through the projector to look at it, and because it gets damaged sometimes I have to take pieces out. Sometimes I’ll reconfigure them or I’ll flip them around so that they can go back in. Or they come out for a while and I re-work them and they come back in at a later stage. Every once in a while you get this ghostly return.

The reason I’m talking about the processes so much is that it deals with the time question. If I put something in the first time and I don’t like it, like there’s not enough happening for example, I’ll just take it out. Now I’m at the stage where I’ll just do two or three or four soaks before it even gets added on.

I think what that does to the time experience is that when I watch the Color Series I’m having an almost one-to-one experience [of time]. It’s a really flat kind of time which can at moments have this other quality to it. If we keep the spatial metaphor its a deeper and shallower sense of time at different points. Whereas when I’m watching Veils, because of all these layers, it is a much more saturated kind of time. I think that that is in the way you experience it—all these processes and palimpsests are available to a viewer, and I think it happens viscerally. I think you understand that there is an incredible compression of time going on. It’s like soaked in paint and soaked in time at the same time, if that’s not too much to assert.

Audience Member 6: I wanted to ask you if you have seen a film by Bill Brand called Rate Of Change?

Madison Brookshire: Yeah, and that’s the precedent I was referring to, and his is scored.

This is a movie I didn’t know about at the time that I made Color Series but of course found out about after. It’s made in a similar way to Color Series in that there were instructions given to the lab, but the score is different because he is really using the zero to fifty scale and so then the…and its one of those funny things actually, because for me they are so remarkably similar in the materials and means of production, and then the experience is like night and day.

Leo Goldsmith: Yeah and there’s a synthesizer soundtrack?

Madison Brookshire: And it’s got titles. That is a movie, you know? This is like stuff that’s analyzed by the projector (laughter), and I’m not trying to make a joke. I mean that’s why we watch the leader go through. For me it is important that, just the way Rothko left the canvases unframed so you could see the canvas and the deep stretch and that becomes a part of the experience of that painting and you can have a very intense experience of just the color itself, but you can also think about this thing as an object. And so for me the object-ness of the film exists in the viewing experience.

Audience Member 2: That reminds me of something else in terms of the framework. I found myself flipping between a scientific documentary framework and an aesthetic relationship. While this is a documentation of the color, it becomes strictly observational, something that you evaluate, count, or measure. And then the aesthetic: the feeling of the color of the affective experience.

Madison Brookshire: I studied with a composer named James Tenney, and the structure of this work is very influenced by the way he would structure things. Often he would find a perceptual phenomenon, usually grounded in the physiological or physio-cognitive way we actually hear sound. He’d find physical properties of sound and then orchestrate them. And that sounds kind of dry, but it is really beautiful music. It’s very moving music, but the structure of it is really not expressionist, at all, but there’s a lot of feeling available in the listening experience.

When I had the parameters set that I was going to use these three lamps, and they were going to go from zero to fifty, and I was looking for a way to organize that, there are certain structures in his music- it’s not totally worth going into but these were based on that. Fibonacci numbers.

Gregory Zinman: Madison, what’s at stake for you making films without a camera?

Madison Brookshire: I don’t know if this is too anecdotal but, when I made Color Series, we had just had our first child and I just didn’t have time. I couldn’t go shoot. What I had was time to sit and work things out on paper. Then later on I could go and really look at them over and over again at the lab.

Gregory Zinman: What about Veils, which is also cameraless?

Madison Brookshire: I don’t know, Its funny. I think of myself as thinking about things a lot, that I don’t do anything without a reason but, I don’t know. There may just be a fear of making pictures for me. On one level I think there are certain things I’m going for that cannot be accessed with representational images, and I’m not interested at this moment in making abstract images with representational means, like unfocusing the lens or something like that. It heightens the experience of the time and the space to just get rid of the other noise, so to speak.

But I don’t know. I actually have another movie that’s all shot, its just I’m still working on it. It was being made concurrently with these. So I’m sorry I can’t give a more considerate answer. Is that good?

Leo Goldsmith: It’s great.