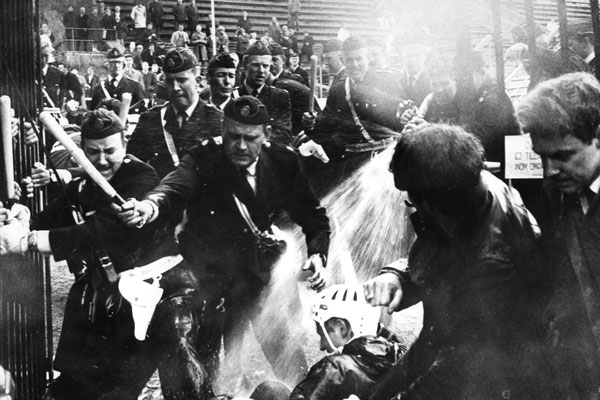

BÅSTAD, SWEDEN: While Ian Smith’s apartheid regime in Rhodesia (now modern-day Zimbabwe) was steadily growing in worldwide unpopularity, its tennis team was paired against Sweden’s for a Davis Cup qualifying match in May of 1968. After Smith executed three Zimbabwean freedom fighters the preceding winter, calls to boycott Rhodesia surged among Sweden’s university students. Well aware of the stigma surrounding Smith’s regime, Sweden’s Police Commissioner advised the National Tennis Authority to host the match in the sleepy tourist town of Båstad. Anti-apartheid activists surrounded the Tennis Stadium in an astonishing direct action, resulting in the first street battles between nonviolent demonstrators and the police in decades. (Some newspapers likened the events to the Great Strike of 1909, while historian Tor Sellström points out that the demos were “as much, if not more, directed against the established Swedish political order as in favour of the struggle in Zimbabwe.”) While the shutdown was an unqualified victory for the students, the authorities would end up holding the match at a secret tennis club months later, in France, where Sweden won 4-1.

A collective of antiwar students took to Båstad with 16mm cameras, and the result is the still-controversial Den Vita Sporten (The White Game), officially credited to “Grupp 13”. The crew included the great leftist filmmaker Bo Widerberg, whose career was stifled by the preeminence of the Vietnam War-supporting Ingmar Bergman (then chair of the Swedish Film Institute); also along was Roy Andersson, then a mere 25 years old. Another member, Ingela Romare, had just finished Revolutions Speak, a five-minute rumination between a mother and her daughter on the leftist slogans on old posters hanging in Stockholm’s Museum of Modern Art.

The White Game chronicles the protest in nail-biting detail: the sloganeering (which included “RHODESIA GO HOME” and “KILL IAN SMITH”), the intersection with other struggles (Mao’s little red books are ubiquitous) and the crackdown on students who jumped a loose gate outside the stadium, beaten by police and sprayed with hoses supplied by Båstad’s firefighters – further proof that the authorities were utterly unprepared for the anti-Rhodesian “hooligans”. It’s also a riveting cross-examination of a so-called “First World” nation determining what it will and won’t stand for: Grupp 13 took pains to document the attitudes of the protesters, the racist Rhodesians who had traveled for the match, the blandishments of official functionaries who had fancied themselves liberal-enough and, probably most crucially, of the Afro-Swedish demonstrators in Båstad. It’s a fascinating look into an anti-apartheid movement eclipsed by that of South Africa in the ensuing decades, and an essential rumination on the overlap between sport and national identity – two items kept separate by power, then and now, when politically convenient.

Special thanks to Johan Ericsson (Swedish Film Institute) and Josh Siegel (Museum of Modern Art).