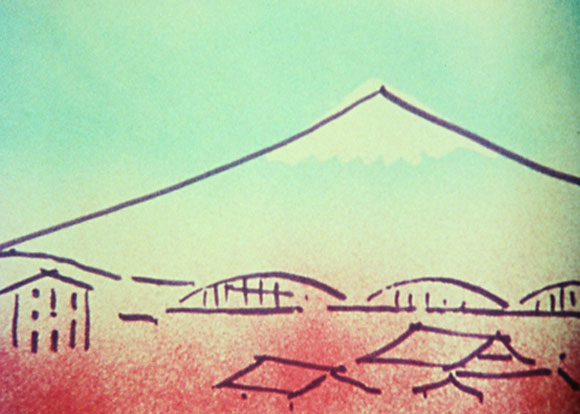

The thesis behind this program is the absence of any single thesis. Superb films come in all varieties, and the best ways to see any film are not through the grid of any particular theory. The history of cinema is glorious in its diversity. If the essence of documentary is rooted in the use of footage of scenes in the world that the filmmaker did not construct, then even Robert Breer’s animated Fuji begins as a documentary, with a snippet of home movie footage of a train trip which Breer then uses to generate all manner of abstraction — before returning to the train footage at the end, thus providing a “lesson” in imaginative seeing not unrelated to the aesthetic of Stan Brakhage. Brian Frye’s Mirror Manhattan has home movie aspects too, being a record of Manhattan seen from the archetypical tourist boat, a Circle Line tour, except that by playing with superimposition and inverting the image Frye suggests more about the vertical density of New York than would be conveyed by more ordinary footage. Christ Welsby’s Seven Days uses stop motion to condense seven days in nature into twenty minutes, but more, he chooses to let his camera angle be entirely determined by the sun, pointing directly at it when it is behind clouds and pointing opposite it when it is shining. Welsby thus also records the rotation of the earth, and also surrenders much more control, in this case to nature, than a typical documentarian gives up. John Smith, one of cinema’s finest humorists, parodies the megalomania of the film director as control freak in The Girl Chewing Gum by accompanying long takes of an ordinary street scene with a voiceover that implies he is controlling everyone’s movements, and even, that he omnisciently knows their purposes.

Susie Benally’s A Navajo Weaver and Shelby Adams and Mimi Pickering’s Mountain Farmer stand a bit apart from the aesthetic, art-aware tradition of the first four films. Both films were spawned by 1960s movements to allow people in distinct cultures to make films — Navajo who had seen little of Western media in the first instance, Kentucky hill people in the second. Both films display a rawness and a lack of artifice, and, especially in the case of A Navajo Weaver, owe little debt to traditional film grammar. Instead they depict, and establish, a direct relationship to the physical world that is rare in its sincerity and wondrous in its sensuality